06 Jan What do you mean by ‘Recovery’?

The following article was originally published by American Stroke Association on January 6, 2021 on their website.

After a stroke, people often ask, “How is your recovery going?”

What exactly do they mean?

What does that question mean to you — if you’re a survivor in recovery?

For many years after Debra’s stroke, we heard it as people asking how she was doing at regaining the capabilities she lost because of her stroke. They might be referring to her walking, use of her right hand, speech – or all of them. In other words, “How is your rehabilitation going?”

Truth be told, once we were “out of the woods” and Debra was in a stable medical condition, recovering capabilities is what mattered most – to both of us. Recovery really did mean rehab.

When Debra was about three years into her recovery, having spent most of her time on rehab, she had made incredible progress. But she was nowhere near regaining all she had lost. She still walked with a significant limp, had no functional use of her right hand, and most consequentially still suffered from aphasia. Her speech was returning, but slowly and incompletely. Did that mean her recovery had “failed” so far? Or maybe was an incomplete recovery? Does a successful recovery require getting back exactly to where you started? We certainly hope not.

Two journeys in recovery

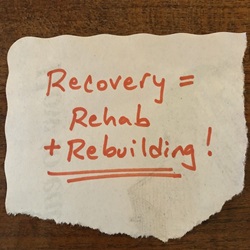

What then is recovery? We have come to believe it’s the combination of rehabilitation AND rebuilding. Rebuilding identity. Rebuilding activities with appropriate adaptation. Rebuilding a rewarding life. Recovery, we think, is simultaneously a physical and emotional journey. It’s the effort to regain lost capabilities, and the effort to rebuild a strong sense of self and a life of meaning, purpose and pleasure. In our experience, and that of so many people we have interviewed and worked with, the word recovery often refers to the physical journey. We believe the emotional journey is equally important, and more attention and resources are needed to support this part of the journey.

Source: Illustration by Steve Zuckerman

It’s interesting to compare recovery language around stroke with that involving the loss of a loved one. We talk about this in Identity Theft in the context of grief, and Debra’s losing her father unexpectedly 25 years ago. Clearly, recovery from that kind of loss can’t be measured by the ability to regain the pre-loss condition. It’s solely an emotional journey evaluated by a person’s ability to push beyond grief and return to life in the face of it. The medical community treats it that way and offers resources to help. That emotional journey in recovery is equally critical after a stroke.

As we look back on our experience, the system we were navigating was telling us that recovery = rehabilitation. Virtually all signals we got from the medical system defined recovery that way – either explicitly or implicitly. We think this does a huge disservice to everyone impacted by stroke.

Embracing the emotional journey

Debra’s academic background and decision to write a book in the face of aphasia launched us on the emotional journey nobody told us about. Fortunately, we stumbled upon it, and then came to appreciate its critical importance. We embraced it for the five years it took to write the book and launched Stroke Onward as part of our continuing process to rebuild our identities and create a life of purpose.

Hopefully, we will be able to help others by shining a spotlight on the issues, working to develop resources, and collaborating with others to change the system we found lacking.

The parallel journeys of physical and emotional recovery powerfully reinforce each other. Many survivors talk about how the hard work of rehab is part of what helps them bounce back emotionally, even if it’s too slow and incomplete.

and Debra Meyerson

Conversely, physical therapists, occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists have told us how sessions are much more productive when survivors are in a “good emotional space.”

“Therapy is much more effective when survivors see it as part of the path toward rebuilding their lives, even if they don’t get all their capabilities back,” said Pam Inbar-Hansen, a physical therapist we’ve worked with a lot. “It lets them focus on the process rather than the result of regaining 100% of their capabilities, a result that is always wanted but most often not possible.”

And just as important, the two paths critically converge. The same therapists, technically focused on supporting the physical journey, can offer critical support for the emotional journey as well. Pam has certainly done that for us, as have many others. And just living your life can, in fact, be great therapy. This is at the foundation of the Life Participation Approach to Aphasia. In this case, 1+1 really does equal 3.

When to focus on the emotional journey

As Stroke Onward works with care professionals to understand what resources would be most helpful to support the emotional journey and how to help create them, we also are wrestling with when they would be most helpful.

Debra spent three years solely focused on regaining capabilities. She wanted her old life back. Margaret Dougherty, an occupational therapist who worked with Deb relatively early in her recovery, stresses the importance of timing with emotional recovery.

“If I had suggested you think about rebuilding your identity and a different life when we were working together, I would have ended up with a black eye, bloody nose or both,” she said. Debra wasn’t ready to hear it just yet.

Conversely, Deirdre Warren, a survivor we wrote about in Identity Theft: Rediscovering Ourselves after Stroke, recognized and accepted the need to build a new life, even as she was pursuing therapy in the early months after her stroke. Everyone has to make their own choice about how much time and energy to focus on rehabilitation, and how much on adaptation and rebuilding. The caregiving system should make critical resources more available to people, offered as survivors and carepartners are ready for them.

“While working in inpatient rehab this past Saturday, a patient with aphasia asked me, “When will I be myself again?” After reading and discussing Identity Theft with book group members and student clinicians, I found myself leaning into a conversation about identity, loss, and change. My patient then spent the bulk of the session talking about her background, family, hobbies, and interests. At the end of the session she said, ‘I AM still myself.”

Sophia Kanenwisher, Speech Language Pathologist and book group clinical supervisor

What can change

Our work through Stroke Onward thus far is validating our belief that the emotional journey really matters – and gets little attention. One of our first projects is to create book discussion guides for Identity Theft. The goal is to make it easier for people to effectively dive into the issues around rebuilding their identities and rewarding lives and help them start or continue their emotional journey.

In collaboration with a highly experienced team, we are testing a discussion guide for book groups involving survivors with aphasia (and sometimes their carepartners). We are also developing guides designed for stroke survivors without aphasia, carepartner groups, professional caregivers and general reading groups.

A second project involves exploring whether it would be helpful to build more content about identity and the emotional journey into the curriculum for degree-granting programs in speech, physical and occupational therapy, and other disciplines serving stroke survivors.

In our initial pilots, we worked with faculty and graduate students at MGH Institute of Health Professions and Boston University’s Sargent College. After reading Identity Theft, virtually all survey respondents felt it would be important to add the book or similar content into the degree-granting curriculum. This issue seems to get much more attention in other countries. We’ve found articles about it from England and Australia, and a Canadian leader in the aphasia community talked in a recent session we led about how they actively incorporate these issues into their care systems. We look forward to learning from our international colleagues.

We are not broken

Part Three of Identity Theft is called “Redefining Recovery,” and in Chapter 17 we wrote:

“After my stroke, I felt broken. So did Sean Maloney, who articulated the jarring recognition that everything can fail. So did Anthony Santos, who wondered when stroke might strike again, and Jim Indelicato, who found himself fearful for himself and his family when he couldn’t be the fixer and protector. So, too, for Ahaana Singh, who felt she couldn’t keep up mentally and others just didn’t understand. Professor Sharon Kaufman observed, “In the year following the stroke, no person we spoke with, even those who had visibly and tangibly regained lost function, claimed to have recovered.”

Does successful recovery require us to regain all we lost? We don’t think so! We encourage all survivors to work long and hard to regain as much as possible. Debra is still improving 10 years later.

But we believe a successful recovery should be defined as rebuilding your identity, and a rewarding life, with whatever capabilities you are able to regain (and retain!), in spite of those you have lost. We think there needs to be many more resources to support stroke survivors and carepartners to achieve that kind of successful recovery. We hope our efforts will help to create some.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.